I started keeping a diary in elementary school and continued more or less consistently until I started grad school a year and a half ago. It’s all there, in a crate in the shed: the movie that was playing when I tasted my first kiss, the outfit I was wearing when I was dress coded in eighth grade,1 the activities I did at camp in the summer of 2007. All the minutiae of a suburban childhood, waiting to be reread, relived, and remembered.

It started, I’m sure, because I liked my pretty notebooks and the feeling of a pen in my hand. I wanted to be a writer, and I knew that writing took practice, so I practiced. It took on a new zeal when I read Anne Frank’s diary in the fifth grade. I was not hiding from the Nazis in an attic, but I drew inspiration from her foreword: “I hope I shall be able to confide in you completely, as I have never been able to do in anyone before, and I hope that you will be a great support and comfort to me.” I did not have many friends; I wanted a confidante. I wrote about the boys who were mean to me, and I felt that it would all be very important someday.

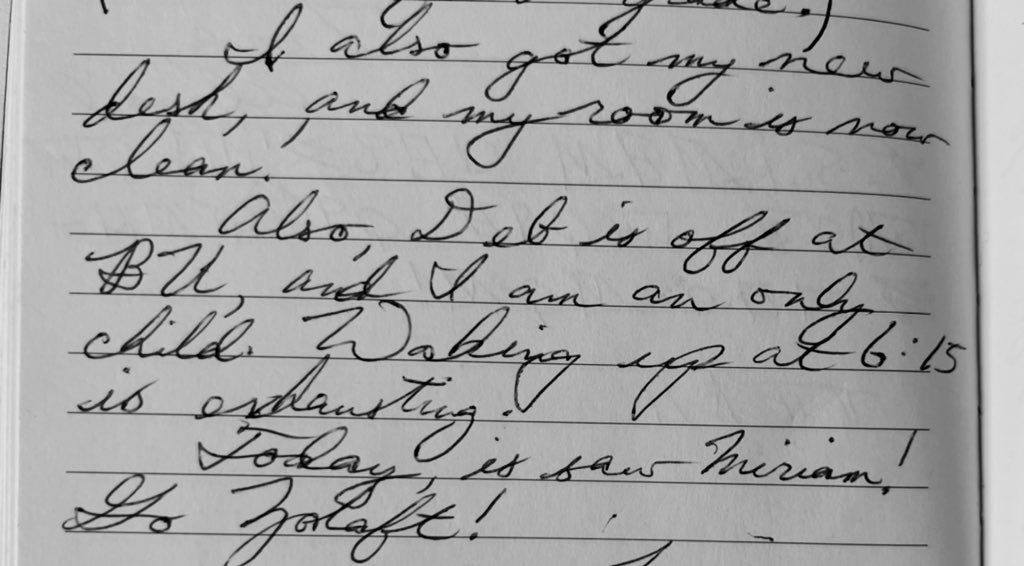

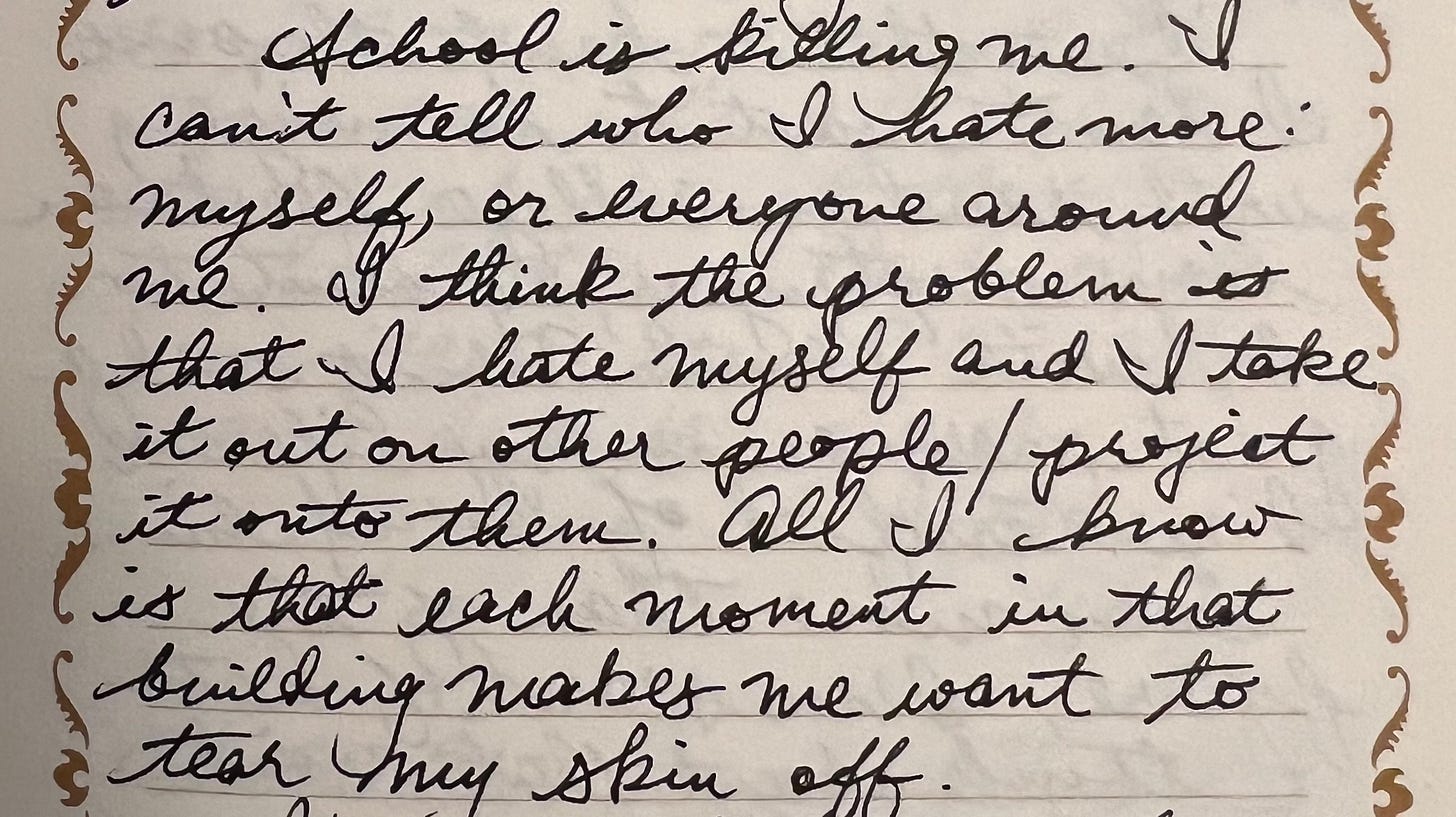

That was all fine, but then I grew up. The more I engaged with my social world, the less I relied on journaling. By my senior year in high school, real-life friends had supplanted my diary as confidantes. I kept writing, but the tenor changed: My notebooks became a repository for negative thoughts. A representative sampling of the melodrama, from 2015:

School is killing me. I can’t tell who I hate more: myself, or everyone around me. I think the problem is that I hate myself and I take it out on other people/project it onto them. All I know is that each moment in that building makes me want to tear my skin off.

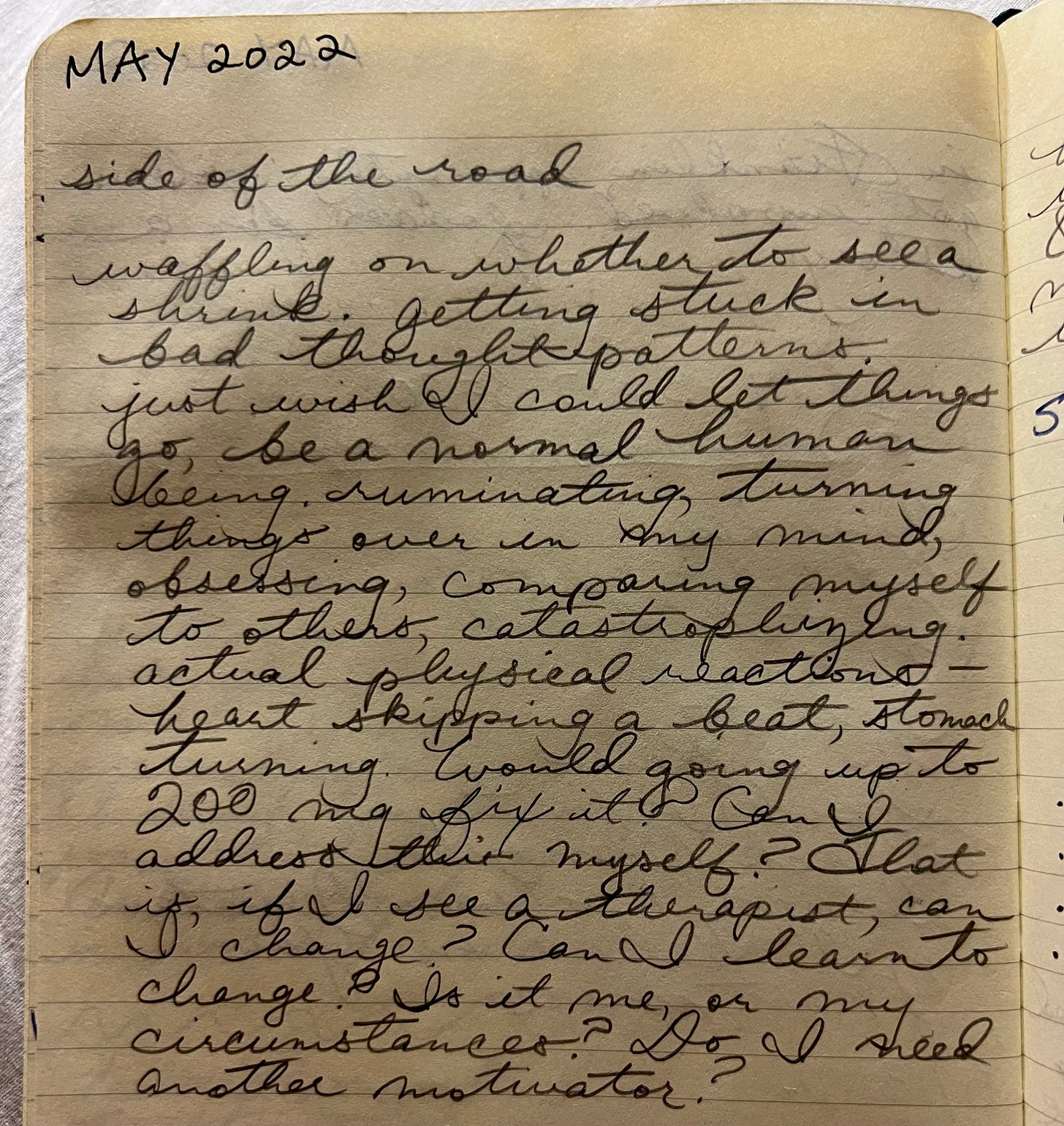

Sometime around 2019, these thoughts veered into what would clinically be called “intrusive.” I wrote them down to try to get them out of my mind, as I had done in the past for awkward social situations and worries that kept me up at night. Somehow, even though I had been diagnosed with OCD at age 11, I did not realize that I was experiencing the second major flare-up of my life (the first having begun in the womb).2 It did not take me an hour to get out of the house in the morning. I did not walk back and forth over thresholds, trying to get it just right so my family wouldn’t die. I had no visible compulsions: just journaling and lengthy sessions of sitting in the bathtub with the shower on, ruminating, promising myself that I would figure it all out by the time I emerged clean and raw. Sometimes I wanted to fact-check a memory, so I would mine my journals and, seeing the misery they contained, walk away feeling much worse. I was harboring these huge doubts that seem so silly in retrospect but that, at the time, made me question every aspect of my identity.

I didn’t realize that the way I wrote these thoughts gave them power, fortified them. After a half-hearted attempt at therapy in Denver, I started my first bout of real-time, big-girl OCD therapy in December 2023. A little late, considering. There, I practiced exposure and response prevention. I learned that journaling could be a compulsion, a way of temporarily assuaging anxiety before it grew back thicker and darker. Still, a common ERP practice is to repeatedly write down the thought that triggers the anxiety. This seemed paradoxical at first: How could writing the same sentence be compulsive and harmful in one context, but therapeutic in another?

It’s a matter of approach. I journaled to relieve my anxiety, to set it on the page and put it away. ERP means confronting the anxiety and stripping it of its power. You say the scary thought out loud. You write it down. You write it again. You read what you wrote. You sit with the anxiety. Repeat until it’s bearable.

I have worked very hard over the past year at abandoning dread. With it, I have abandoned the inclination to preserve. I recently encountered something that struck me as wildly liberating: During a class trip to the Fowler Museum at UCLA, a curator of the Fire Kinship exhibit explained that museums tend to collect and preserve materials, without much thought for when to let them go. Several of the artworks at the exhibit are ephemeral, including Leah Mata Fragua’s hand-dyed cotton poppies and Lazaro Arvizu’s sand installation. If art can be disposed of, so can my memories. I am learning to forget.

This summer, Will reminded me of a joke I made when we first met. I had said that I lost out on best dressed in high school to someone who had bought her success, like the Yankees. Apparently I meant that the student body favored designer brands over thrifty style. It was jarring to hear this joke repeated back to myself. It sounded like something I would say, but I had no recollection of ever saying it.

That was the first time that I really grasped that there are versions of ourselves who live in others’ memories but are unknown to us. I might be able to locate, in my journals, how I felt or what I did on the day I told that joke, but the essence of that interaction lives in Will’s mind alone. My journals couldn’t preserve the moment any better than they could assuage my angst. So I’m giving up the urge to archive all of life’s minutiae. I’m making my memories among the living, instead.

Yeah I’m still bitter about something that happened 14 years ago. Jan. 29, 2011: What’s wrong with me? I cried in school the other day over the stupidest thing. I was wearing a pair of leggings, a T-shirt, and a long sweater. During science class, Ms. N pulled me into the hallway and had me turn around. She said she had been instructed to take a look and see if what I was wearing conformed to the dress code. Really, she just wanted to make sure that my sweater was covering my butt.

I asked her what teacher had asked her to check, and she refused to answer. I said that I had seen [the principal] in the hall earlier and she hadn’t said anything, but then I put two and two together. I said, “It was [the principal], wasn’t it? Why didn’t she say it to me herself when I saw her in the hall?”

Ms. N said that [the principal] was on her way to a meeting upstairs, and that she didn’t want to have to call me up to the office or anything. But right then, I don’t know why, but I burst into tears. Maybe it was the fact that [the principal] took it unto herself to look into whether or not I was “inappropriately dressed” (which, I can assure you, I was not), or maybe it was that I was mad at myself. It was so embarrassing then, having Ms. N addressing my mental circumstances and all.

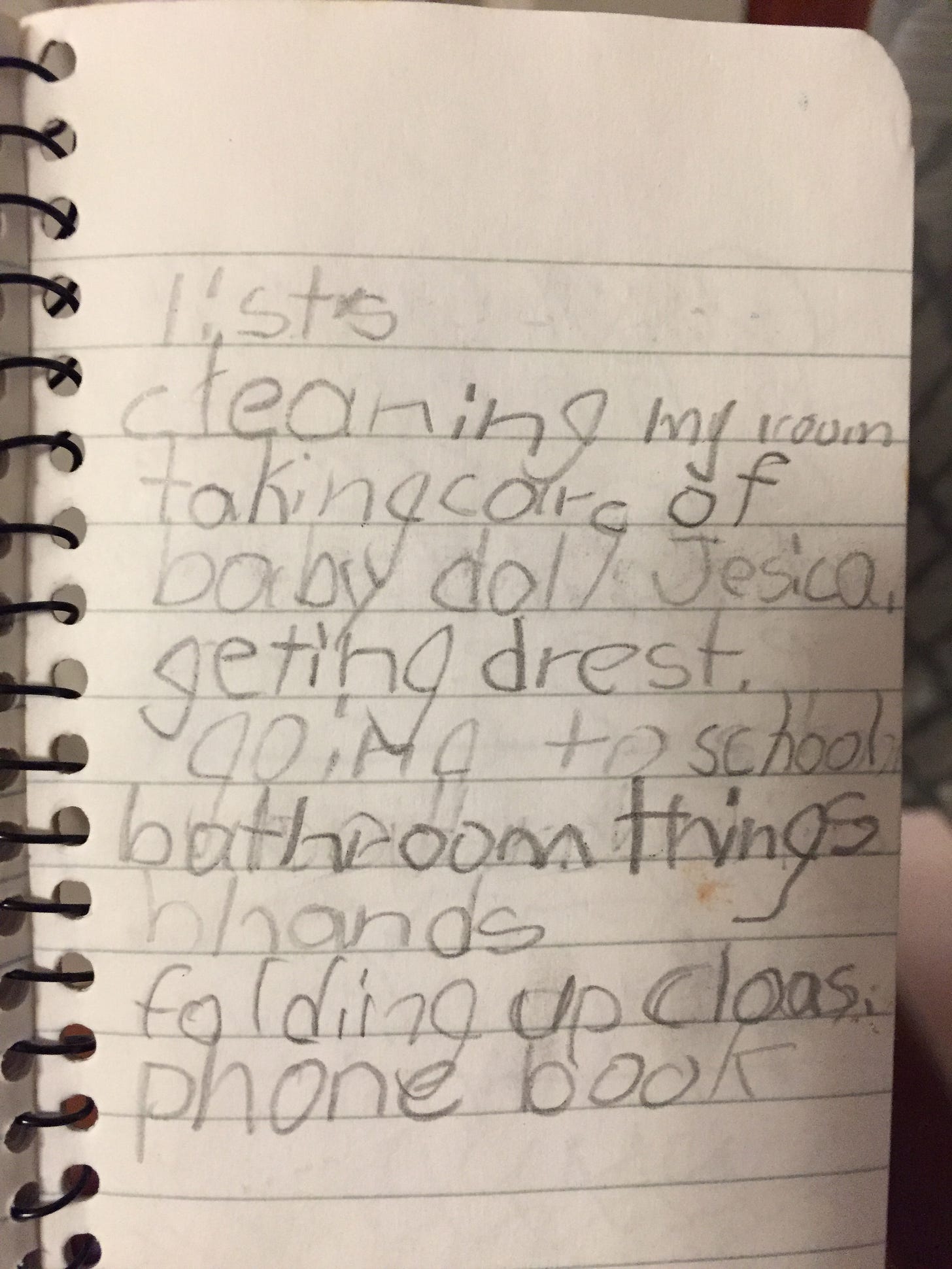

As a child, I recognized my fears to be irrational and hid them from everyone, my diary included. However, when I was going through things at my parents’ house a few years ago, I found this list I made in 2004, when I was 7. I had included OCD rituals as part of my to-do list. “Bathroom things” was an elaborate ritual I did every time I used the bathroom, so that nothing bad would happen. “Hands” referred to compulsive hand-washing.

hey! thanks for sharing. such an interesting topic.

i too have recently questioned my urge to journal the bad things that happen to me. i used to write lengthy entries detailing exactly how i would feel, which, in some of my worst moments, would include a list of all the things that make me abhor myself, or even more morbid stuff. but i then was like is this really helping?? and i reached a similar conclusion than yours: not really

i still keep muy journal, but for organization and keepsake purposes. however i have stopped compulsively writing whenever i feel sad or mad or unhappy. i think it's for the best

I was thinking similar thoughts just this morning. I journaled from 16-21 and again from 25-28 and while I enjoy the practise, I noticed a cycle I don’t like: the more I’m unhappy at any one time, the more I journal. To the point it becomes a comfort of my day that feels unmovable and inhibits me from doing the shit that would fix my issues.

I hate it when people overdo the romanticisation of their own pain so idk why I’ve allowed myself to do the same thing